Featured Articles

Overview for this article:

1. Introduction 2. Revere, the Huguenot’s Son 3. The Bell Ringer

4. Revere’s Education 5. The Silversmith 6. The Dentist 7. The Engraver

8. The Son of Liberty, Express Rider 9. “THE RIDE” 10. The Powder-maker

11. The Soldier and Cannon-maker 12. The Supporter of the Constitution

13. The Bell-maker 14. The Copper-maker 15. The Philanthropist 16. Conclusion

17. Questions for reasoning

(December 22, 1734 - May 10, 1818)

There is a saying, “jack of all trades, but master of none.” Yet in the case of Paul Revere we find an example of one who had the character to master many trades as he served our nation in many capacities. He is only in our memories for his midnight ride, made famous by Longfellow’s poem. A closer look at his life reveals a fascinating individual who contributed greatly to our nation during its dawning and following. His character is seen in this quote from the children’s book: And Then What Happened, Paul Revere? “Of all the busy people in Boston, Paul Revere would turn out to be one of the busiest. All his life he found that there was more to do, more to make, and more to see, more to hear, more to say, more places to go, more to learn than there were hours in the day.” His was a life spent in action spurred by principles during the ever-changing world around him of colonial days, Revolutionary days, and post-war days of the new nation. His was a life of industry and ingenuity.

Revere, the Huguenot’s Son

Before we see this patriot at work let us first take a glimpse at his ancestors from France and their love of liberty. Even before Paul Revere’s birth we are reminded of God’s hand of protection as his father Apollos Revoire crossed the Atlantic around 1715. He was thirteen years old fleeing from persecution by the Roman Church (in France under King Louis XIV). He was a religious refugee coming to America for religious freedom. He had first been sent by his parents to an Uncle Simon in Guernsey, a small island in the English Channel. His uncle gave him money and put him on a ship to America. A storm rose while crossing the Atlantic. This one who would later be the father of a great patriot was almost lost at sea. Forbes wrote, “God brooded upon the face of the waters. His hand parted the mountainous waves. He upheld the ship…” God had protected Father Revoire and the future son, Paul. Love of freedom was found in Paul Revere’s parents and grandparents. The same love of freedom would burn in the heart of this patriot, Paul Revere.

Apollos made it to Boston. “Already Boston was something more than a geographic fact-something of a state of mind.” Boston was almost an island connected by a narrow strip of land. It had three large hills and many small ones… Long Wharf was two thousand feet long and deep enough for the largest boats of their day. Apollos was to be apprenticed for ten years to John Coney. Coney was a respected, religious, and successful goldsmith and silversmith with a thriving business of working in silver. Revoire’s master died before the end of his apprenticeship. He was able to raise the money to pay the estate for his freedom. He set up as a goldsmith in Boston. He changed his name to Paul Revere because Revoire was too hard to pronounce. He was a “self-made man in the bright new world of British America. In 1729 he married Deborah Hitchborn, a New England Puritan who came to Boston during the “Puritan Great Migration.” There were eleven brothers and sisters. Five died in childhood and two as young adults.

Paul Revere , the son, was born in Boston on December 22, 1734. While Paul Revere, the father, was trained as a silversmith by one of the best in their day, nothing of his work remains. “It is the son after him-Paul Revere- who seems to have served a spiritual apprenticeship to John Coney.”

The Bell Ringer

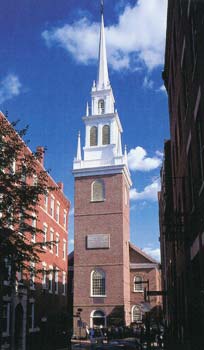

The Reveres attended the Cockerel Church, a congregational church. Young Paul found a way to earn money at another church-Christ Episcopal, also called the Old North Church and the Eight Bell Church. This church celebrated Christmas while some didn’t. It had eight bells. In 1750 when Paul was about fifteen years old, he and six other boys founded a bell-ringers association to ring the bells one evening per week for two hours. They were under the guidance of an experienced bell-ringer who taught them the art of bell-ringing. Bells were used to communicate to the community special events as well as times for worship.

The seven boys drew up a covenant contract. In David Fischer’s book, Paul Revere’s Ride, he describes it in this way. “That document tells us many things about Paul Revere and his road to revolution. These boys of Boston drew up a solemn covenant, and instituted a government among themselves very much like Boston’s town meeting. They agreed that ‘we will choose a moderator every three months whose business shall be to give out the changes and other business as shall be agreed by a majority of votes then present…all differences to be decided by a majority of voices.’ Membership was restricted as narrowly as in a New England church or town. The boys decided that ‘none shall be admitted a Member of this society without unanimous vote.’ They also…promised to work for their rewards: ‘No member’, they voted, ‘shall beg money of any person.’ This simple document drawn up by Boston boys barely in their teens summarizes many of the founding principles of New England: the sacred covenant and the rule of law, self-government and majority vote, fundamental rights and free association, private responsibility and public duty, the gospel of service and the ethic of work, and a powerful idea of community.” What an example to our youth today of applying principles of liberty in a money-making enterprise of this sort!

The steeple of Christ Church was known for its beauty and the bells. The weight of the bells ranged from one thousand five hundred forty-five pounds to six hundred twenty pounds, with the inscription, ‘We are the first ring of bells cast for the British Empire in North America…1744, by Abel Rudhall’. (However, the church would later be made famous, not by its British-made bells but by “its American-made Patriot and the two lanterns that hung as signal for that famous midnight ride”.) The steeple of the Old North Church was also a look-out place where Revere learned the details of his city of Boston. He later used “the knowledge to become an excellent map-maker” later in life.

Another influence on Revere’s life was the preaching of Jonathan Mayhew at the West Street Church where Mayhew preached against arbitrary rule. It was here (Forbes) “in January of that year young Mr. Mayhew fired what John Adams was to call the opening gun of the Revolution.” Revere heard the preaching of ideas of civil liberty.

Revere’s Education

Paul’s schooling aimed him toward being a craftsman, as his father. Grammar schools prepared boys for being lawyers, doctors, and ministers. Writing schools prepared boys to become artisans, craftsmen. His father taught him to be a silversmith. About education of their day and his schooling Forbes says, “The boys were not educated in the modern sense of the word, only given the rudiments by which they might educate themselves later on.” He attended the North Writing school for about five years. The test of his education was that later on he was able to read ‘chemical essays’ and other works related to his work. He also loved books.

The Silversmith

The Reveres lived near the head of Clark’s Wharf which depended a great deal on sea trade. Paul was apprenticed to his father to be a silversmith. He learned the trade so well that when his father died he was able to carry on the business. He was only in his late teens. This showed the level of maturity and his strength of character and ability. He became the head of the household. For a time when he was twenty-one years old he served in the French and Indian War in 1756. Then he returned to his work as a silversmith. (Forbes) “Paul Revere did push out some frontiers for his country, but they were not so much geographic as industrial, Boston-not Albany was to be his base.”

At age twenty-two Revere was a master silversmith. Here is a description of his character that was demonstrated throughout his life. (Forbes) “ Bold is the adjective his contemporaries used most often for him. As ‘bold Revere’ he was sung on the streets and in the taverns of Boston. But to this is also added ‘steady, vigorous, sensible, persevering, or cool in thought, ardent in action.’ A nice balance between good sense and boldness characterized his whole life. It is not a rare combination, but when to it is added intelligence, fine workmanship, and a certain robustness half physical and half spiritual- a great deal may be accomplished.”

Paul became a leader in the artisan class. Leaders of the Revolution wanted sympathy of the artisans. Paul provided leadership and became a powerful voice for the craftsmen class.

Paul married Sara Orne August 17, 1757. They had eight children, of which three died in infancy. After Sara passed away Paul married Rachel Walker. They had eight children, three of which also died in infancy.

The style of his work was the rococo style. “In this, his first period, his craftsmanship was the most perfect. Rococo with its cast shells and scrolls can easily be overdone….Its danger is over-decoration…Paul Revere always handled this dangerous fashion with restraint…The size and importance of his orders show that his workmanship and artistic ability were thoroughly appreciated by his contemporaries…he was considered the best of all the silversmiths who worked in America during his lifetime. There was more variety to his work than to that of any other silversmith. More of it has been preserved. Probably as many as five hundred of his pieces are known to exist…(not including those owned in private homes) During this period-roughly up to the Revolution- he marked his work with a little ‘pellet’ before his name. It is the ‘pellet Revere’ that is on the whole considered his finest silver. He was in full stride as an artist before he was thirty.” After the Revolution styles began to change and so did Revere’s style. “Paul Revere was no hermit living and working in a vacuum. Everything he did…was in response to changing needs and modes of his own day…With the rise of the Republic came a new fashion in architecture, furniture, and silver, with emphasis on classic purity…(the Federal style). The Federal’s lack of personality makes it more suited to everybody’s taste. Its light strength and grace are impossible to dislike…Its perfect gentility suits oddly with the new aristocracy, who, however, liked it and bought it.”

The Dentist

In 1768 Revere launched out into another field, which was related to silver-smithing. That was the field of dentistry. American teeth were in very bad condition. Revere learned how to make false teeth from John Baker. He was not a dentist in the full sense of the word, but could clean and set false front teeth. When Baker left, he referred people to Revere for their needs. (After the Revolution, Revere dropped this trade.) It is interesting to see, though Revere did not further the field of dentistry himself he had two young neighbors who came into his shop who would. They were Josiah Flagg Jr. (his father had been a bell-ringer and later published music with Revere) and John Greenwood. He is known for designing the first dental chair. Josiah grew up to be famous for his contributions to the field of dentistry. John later in life became George Washington’s personal dentist. He was the one who made the set of false teeth for Washington. They were made of hippopotamus tusk, not wood. “It is a curious coincidence that, just at the time Paul Revere was practicing his simple arts at the head of Clark’s Wharf, these two small boys were his close neighbors…Paul Revere’s greatest service to the science may have been the good-natured way he answered their questions, and let them watch him as he wired in the teeth…”. During the Revolutionary war it was Revere who was the first to use forensic dentistry. He identified the body of a patriot who died during the Battle of Bunker Hill, Joseph Warren. Revere had done work on his teeth. During the British occupation of Boston the British had disrespectfully buried him in a common unmarked grave. Revere was able to identify him and Warren was given a proper burial.

The Engraver

The art of engraving was done by cutting stones, metal or other hard substances for making pictures. In the 1760’s because of the Stamp Act times were hard in Boston financially. One thing Revere did to earn money among others was engraving. He published with Josiah Flagg ‘A Collection of Psalm Tunes, in two three or four Parts from the most celebrated Authors fitted to all Measures and approved of by the best Masters in Boston, New England.’ Revere did the engravings for the music book. Later he did engravings for another singing book by Edes and Gill. It was common during their times for engravers to ‘borrow’ designs from others. Revere was no exception. He taught himself the art of copper-plate engraving. He was a master at engraving on silver, but not so on copper. “His work on copper has little to recommend it except its humor (sometimes unintentional) and historic interest.”

During this time in history both Europe and America were involved in political and social engraving. Revere’s work was artistically inferior spurred mainly for financial and political purposes. His work was dependent upon the drawings of others.

In 1768 the colonists boycotted English manufactured goods because of the Townsend Act. “The king demanded that the Massachusetts General Court ‘recind’ a circular letter sent to the other colonies…Seventeen members recinded. Ninety-two refused to recind. In their honor Paul Revere was commissioned by fifteen Sons of Liberty to make a large and handsome punchbowl.” It was decorated by the thoughts of the fifteen Whigs including the words ‘Magna Charta’, ‘Bill of Rights’, and ‘glorious 92’ along with the fifteen donors’ names and Paul Revere’s. (Ninety-two became the number to represent the Patriots.) Revere then made a copper engraving of the seventeen who recinded dishonoring them in very graphic terms.

In 1768 British troops landed in Boston at Long Wharf to be as a ‘police force’ to control the rebels. Their ‘insolent parade’ created a great stir in Boston and their presence a great unrest. Revere’s engraving of this landing of the soldiers became one of Revere’s most famous engravings. It was published in the Boston Gazette. The ’lobster-backs’ were quartered all over Boston. This along with their presence on the streets caused great unrest and friction between the whigs and Tories.

“A year and a half passed, with street fighting…passive resistance; angry words, and petty insults, yet also petitions to the Crown which are still honored landmarks in man’s struggle for representative government…Yet this almost-normal life was only a thin crust over a molten mass of dissatisfaction, patriotic determination to win representative government, resentment and hatred. The crust held for eighteen months.”

On the fifth of March, 1770 there was the sad event of the Boston Massacre where five died by the shots of the British soldiers who had been taunted with snowballs, shells and insults. The town was very volatile with three different mob-groups converging that day on King Street. Montgomery, the soldier who first fired, shot Crispus Attucks. Other shots followed until five lay dead and dying. The soldiers involved were later defended unpopularly by John Adams who to his own merit believed in law and order and was on the side of right.

Revere made an engraving diagram of King Street and the massacre. It was used for the trial of the soldiers showing the locations of the bodies and those involved. His accuracy and information showed that he was probably nearby during this event. Later Revere made an engraving of ‘Five Coffins for Massacre’ which was used in the Boston Gazette. Revere then did his most famous engraving of the Massacre,“ prints done in color to be sold in the streets. These showed the bright red of the British coats and the red of the Yankee blood with the red of gore and lobster-backs…Generations of children learned to hate England by gazing at these crude prints. Revere was primarily interested in the political aspects of his print, not in its art nor accuracy.” It did not portray an accurate picture of what took place and it demonstrated the outrages against the king by this extreme taken by a patriot in his engraving. He, however, did not make the drawing for it, but ‘borrowed’ it from Harry Pelham. This was discovered by a letter to Revere by Harry Pelham accusing Revere of using Pelham’s picture. Their two pictures show strong resemblance proving that the engraver had ‘borrowed’ heavily from Harry Pelham. While Pelham’s letter showed strong dishonor and dislike for Revere we find them reconciled by being somewhat involved in a business partnership together later on.

During the time of the Boston Massacre the Townsend Act (taxes on many things) was abolished-except the tax on the tea. The march for representation continued for conscience sake.

In 1774 Revere did a great deal of engravings. He copied old illustrations in Captain Cook’s voyage for James Rivington of New York for a new edition along with a map. He did work for Isaiah Thomas’s Royal American Magazine. Revere did numerous engravings including “his third view of Boston and some unflattering likenesses of John Hancock and Sam Adams, a portrait of a jumping mouse common to Russia, among other things. At least two of his prints were based on the work of Benjamin West.”

After the Boston Port Bill (closed Boston’s port until the tea was paid for) Revere did a cartoon of Boston being strangled. After the Lexington and Concord battles in May of 1775, “the Provincial Congress in Watertown engaged him to cut copper plates and print money for the colony. He went to Watertown and immediately settled down to work.” (In 1786 Revere made an engraving of George Washington which he sent to his cousin, Mathias in France.)

The Son of Liberty, Express Rider

When Paul was twenty-five years old he was received into the Society of the Free Masons. ‘Paul Revere, a Goldsmith and engraver as Entered Apprentice.’ “He was entering a carefully selected group based on neither wealth nor prestige, but entirely upon character.”

After the French and Indian War, the cost of it fell heavily upon the American colonies. To enforce the Navigation Acts and collect money Writs of Assistance allowed British officials to search ships for the purpose of collecting customs. Revere through his associations with Masons and others in Boston began to move among leaders of the cause for American freedom who opposed the unjust acts of the King. James Otis, Samuel Adams, John Hancock, John Adams and his close life- long friend Dr. Joseph Warren were among his associations. Such a variety of character and abilities formed the Whig party as we see the contrast of John Hancock and Paul Revere. (Forbes) “Soon Samuel Adams was bringing him (Hancock) to the Whig clubs, in which Paul Revere was beginning to stand out as someone worth watching- a man capable of bridging the very real gap between the thinkers and the doers. Revolution was making strange bedfellows, but none stranger than the hard-working unadorned (he did not even powder his hair nor wear a wig) young silversmith and this finicky, overdressed young man of great prosperity.”

With the Stamp Act of 1764 ( a tax on legal and other papers) two groups arose. “The opposers of the measures of the administration were termed whigs, Patriots, and Sons of Liberty; and the supporters were called Loyalists, Tories, and Friends of Government…The whigs, traced by the lineage of principles, had an ancestry in Milton, Locke (and others) , or the political school whose utterances are inspired and imbued with the Christian idea of man. Their leading principle was republicanism as it was embodied in the free institution of the colonies…”. Revere became one of the leaders of the Sons of Liberty. Through the Committee of Correspondence the unlawful arbitrary actions of the king were communicated throughout the colonies and the principles of the Republic were expressed.

In 1766 with the repeal of the hated Stamp Act a great celebration took place in Boston. A huge decorated obelisk was made which held three hundred lighted lamps was paraded to the Liberty Tree (meeting place for speeches). Revere made a copper plate dedicating it to every Lover of LIBERTY. The Liberty Tree itself was decorated with flags and banners. Then the whole town joined to hang lanterns on it. It was called The Great Illumination , the day of a great demonstration of the love of liberty as they celebrated a small positive but important moment of victory.

During this time express riders were used to send out messages. Revere was often chosen to ride express for matters of great importance. In November of 1773 when the Dartmouth landed in Boston harbor with taxed tea “Paul Revere and five other men were chosen to ride express to warn neighboring seaports that the tea ships may try to unload. Revere took part in the Boston Tea Party in December of 1773. Though Revere may have been recognized and was older it was decided that some of the older men would go to keep order. “He went although by doing so he risked his little house on North Square, his horse, his liberty.” After this event while the other Sons of Liberty slept, it was Revere who was chosen to ride to New York and Philadelphia to spread the news. He rode sixty-three miles a day and was back in Boston on the eleventh day. He went on many missions of this nature always ready to warn the country when called upon. “During the next year Revere rode to Philadelphia and back four times. In 1774 Revere delivered the Suffolk Resolves to the Continental Congress in Philadelphia written by Joseph Warren. For the principles stated in them Warren himself was to die, and so Revere carried principles of liberty as he rode express. “Revere rode thousands of miles as express for the Boston whigs. There were plenty of men to choose from. It would not be hard to get both a discreet man and a good rider, but he was their first choice for their hardest work.”

There were three caucuses, where town meetings took place run by the whigs in Boston. Revere attended the North End artisan group. While these Sons of Liberty were referred to as ‘mob-rule’ they were a trained mob who never took one life in Boston nor inflicted permanent physical injury. Just as the masons had their secret adornments the Sons of Liberty wore a secret medal about their necks. Two lists of the meetings were preserved from that day (1774-1775), probably by a Tory. Paul Revere’s name is found there with the description: “Silversmith, Ambassador from the Committee of Correspondence of Boston to the Congress at Philadelphia.”

What sort of horses would have been used for the express riders? The New England horse was developed to carry a rider or pull a light-weight wagon. Their colors were often sorrel, bay, black, dun, but not often white or grey. Some strains of breeds were the “Clark” horse, Suffolk Punch, Andalusian, the Naragansett pacers, and the Yankee Hero. The riding horse was usually small not often higher than fourteen hands. One of Revere’s was described as a “large, homely horse, six years old this spring and perfectly broke to any kind of harness and very very sound. I believe you will find him as good as he is homely.” In 1773 he owned a mare, not for his business but for “pleasure and because he liked horses…A love of horses must have gone back to his childhood: perhaps as he hung about the Hutchinson stable and coach house, and earned a penny leading a horse to the mounting block waiting for the master… The horse Revere rode on the Famous Ride was probably a plain lively surefooted little creature, who paced naturally, was as enduring as the Arab, sorrel in color, and would get him to where ever he was going…”

“THE RIDE”

December of 1774 finds two key personal events in Revere’s life. He turned forty and Rachel (his second wife) had their first child, Joshua. On the political front General Gage, planned to send soldiers to Portsmouth to strengthen Fort William and Mary. Revere was chosen to ride express to warn the fort of the coming British reinforcements. With soldiers quartering in homes throughout Boston (by the Quartering Act) people were not free to come and go without a pass. He got a pass and rode to the fort sixty miles. They got the gun powder out of the fort and hid it under the pulpit of the meeting house. General Gage’s “expedition to Portsmouth had miscarried through Paul Revere’s efforts.”

This marked the first direct attack of the colonists upon the British. Everyone who took part, including Revere, were marked men. “Nothing the Yankees had done thus far so enraged George the Third personally as this seizure of his fort and his supplies…He demanded the punishment of every man and the immediate seizure of all rebel supplies. The result of this policy was Lexington.”

During the winter of 1774-75 the Charles River never froze. While it helped the British by keeping help away from Boston because they couldn’t cross the water, “this freak of nature was a blessing to Boston… of whose inhabitants were poverty struck and without firewood.” This was also a help to Revere and his self-appointed committee of mechanics (artisans) who patrolled Boston secretly during the day and winter nights. Every time this group met they swore on the Bible to not tell anyone of their actions or discoveries except the leaders of the Sons of Liberty.

General Gage knew of the American’s ammunition at Concord. The king had ordered to seize it. He sent spies to spy out the way to Concord, stores at Worcester, and Lexington. He planned to capture the leaders of the cause, Sam Adams and John Hancock who were at Lexington. The route to Concord would be ‘partly by water, with only a few miles to march.”

On April fifteenth, “Revere and his associates knew that something was up. The boats for transport had been launched and grenadier and light infantry were all taken off duty.” Many of the American leaders had already left Boston. Joseph Warren was still there and Revere. “That Saturday night it was decided between them that Paul Revere should next day warn Sam Adams and John Hancock )whom they knew to be stopping at Hancock’s relatives, the Clarks, at Lexington). Also, the stores at Concord were a probable object. They must be hidden.”

“On Sunday, probably starting before light, Paul Revere made this trip seemingly without undue haste or incident. He found the statesmen…at the parsonage close by Lexington Green. The Provincial Congress…at Concord had adjourned the day before, not to meet until the middle of May. It was impossible for the Boston delegates to return to Boston, and very shortly they must start to Philadelphia for the Second Continental Congress…” There at the Clark house John Hancock had numerous things including a trunk which held papers “so treasonable they must not fall into British hands. It was removed to a nearby tavern, Buckman’s Tavern. Sam Adams traveled much lighter, “never needed anything but a pen, ink, and paper. As crisis followed crisis, his spirits always good rose…He faced the gathering storm clouds without qualms, without doubts. America should be entirely free. To this end he had devoted his life…If blood must be shed, very well, let it be shed, a great nation was struggling to birth.” Paul Revere had given the warning. The statesmen would be ready to escape. Concord was warned that day. The Patriots hid the ammunition for safe keeping and the militia prepared for action, ready at a moment’s notice for the British regulars.

Towering above the mouth of the Charles River is the tall spire of Christ Church (the Church of the Eight Bells, the old North Church). Revere chose this steeple for the signal lanterns because it was at that time the tallest steeple in town, one hundred ninety-one feet. Also, Robert Newman, the sexton (custodian) would be able to unlock it in the middle of the night. He too was a Patriot. Revere on his way back to Boston stopped at Charlestown and “hunted up William Conant, a prominent citizen high in military circles, and a Son of Liberty. He told Conant ‘that if the British went out by water we would show two lanterns in the North Church steeple-and if by land one as a signal, for we were apprehensive it would be difficult to cross the Charles or get over Boston Neck…Watch then, for the lanterns in the spire.’ ” He then went on to Boston. He and the ‘Committee’ were on the watch for British activity and plans. Once the news of which direction the British were going was learned, Revere’s lantern signal plan would then begin. (Contrary to Longfellow’s poem, the signal was to be from Revere, not to him.) The reason for the lantern signal was to alert Conant in Charlestown in case Revere got captured without making it out of Boston with the news. Conant would then send the news by express rider to Lexington and Concord.

On Monday, April 16th things were tense for the British with numerous conferences with Gage and his officers. General Gage did not expect the rebels to take up arms. He thought ‘this’ would all be over in a short time without incident. “Only two people were told the destination of the regulars- Lord Percy and Gage’s own wife.” Not even the soldiers knew their destination. Little did they know what awaited his soldiers. On Tuesday, April 17th Gage sent troops to catch Revere or any other messenger who would try to reach Concord. Traps had been set for Revere in a number of places. By the time the soldiers left they probably knew their destination, for one of the officers grooms let another groom know, who had pretended to be a supporter of the king. It was that groom who told Revere, along with two others. The soldiers were preparing to march. Word was out from someone (some say by Gage’s American wife) that Concord was the destination.

At ten p.m. on Tuesday Dr. Warren sent for Revere to go to Lexington to warn Adams and Hancock the regulars were on their way. Express rider, William Dawes had been sent earlier as well. Revere went to Robert Newman who was waiting for orders. They went to Christ Church. Newman took two lanterns from the closet “and softly mounted the wooden stairs Paul Revere’s feet had once known so well as a bell ringer. He climbed past the eight great bells…until he came to the highest window of the belfry…Beyond was Charlestown, and there he knew men were waiting, watching for his signal. He lit them…probably displayed his lanterns for a moment only…(They were out by the time Paul Revere had crossed into Charlestown.) In spite of the poem, they were not a signal to Paul Revere, but from him.” He was out that moment still in Boston. Revere went home and prepared to ride. He however, forgot his spurs and something to muffle his oars, as he crossed the Charles River in North Boston past the British warship Somerset and then to Charlestown.

The British boats were going back and forth on the Charles River carrying the regulars from Boston to Cambridge which is a short distance west of Boston. They would be leaving from there for Lexington and Concord. This route “by sea” was a slightly shorter route than going “by land” from Boston by way of the Boston Neck south of the Charles River. It would give the Patriots less time to prepare, so they thought.

Revere found in Charlestown Richard Devens, of the Committee of Safety who had sent word to the Clark parsonage that British regulars were coming to get Adams and Hancock, knowing that messenger would probably be caught. “Revere himself might have better luck.” He would need a good horse. John Larkin was one of the wealthiest citizens. It was his best horse that was now turned over to Revere…(In the geneology of the Larkin family there is mention of “Samuel Larkin, John’s father of Brown Beauty, the mare of Paul Revere’s ride.). At one point near Charlestown Revere was almost captured by British officers before the Ride even began. “One tried to get ahead of me, and the other to take me…The one who chased me endeavored to cut me off, got into a clay pond…I got clear of him and went through Medford.” (wrote Revere later in his account of what happened). “Now for the remainder of the night Revere’s success, perhaps his life and the lives of others, would depend upon this horse…And now it was eleven o’clock…He eventually rode about twelve miles to get to Lexington and Concord was six miles farther on…With the hundreds of miles he had ridden the last few years, he would be able to judge well how to pace himself…(Five hours later would find the horse in excellent condition though much was to happen to Revere). So away down the moonlit road, goes Paul Revere and the Larkin horse, galloping into history, art, editorials, folklore, poetry; the beat of those hooves never to be forgotten. The man was…not merely one man riding one horse on a certain lonely night of long ago, but a symbol to which his countrymen can yet turn. Paul Revere had started on a ride which, in a way, has never ended.” As Revere rode he gave the alarm to almost every house from Medford to Lexington.

Revere and three others were captured before making it to Concord. (Only Prescott got through to Concord.) Those who captured him were told to shoot if he tried to escape. As they were going to Lexington an alarm shot to alarm the country was heard. Major Mitchell turned them loose without horses taking the Larkin horse. Revere then went to the Clark’s house and told Adams and Hancock what had happened and of the coming of the British. Revere went with them for about two miles. He then returned to get Hancock’s trunk to safety. In Lexington he and Hancock’s secretary, Lowell, went to Buckman’s Tavern to get the trunk while the British soldiers prepared for a full march. Revere saw from the upper window of Buckman’s the British soldiers lining up on the Green and the American minutemen. While getting the trunk the famous words were said, ‘Don’t fire unless fired on, but if they mean to have a war let it begin here.’ “With that simple absorption on what was to be done at the moment, which characterized the whole man…” while carrying Hancock’s trunk across Lexington Green the ‘Shot was fired that was heard around the world’. He had turned his head, seen the regulars dash forward, heard their shouts- but gone on with the trunk….One of the horses bolted for the Clark’s parsonage. He was a Yankee horse captured during the march, carrying Sutherland. Some believe it could have been the last appearance of the Larkin horse…Revere’s was the only one we know that they took possession of, and certainly Revere’s horse would have headed for the Jonas Clark parsonage- it was the last place he had been fed…John Lowell, Revere and the trunk were now at the parsonage…Adams and Hancock moving still farther away to safety…They too heard the rattle of musketry. Adams with prophetic utterance of his country’s dawn of independence exclaimed, “O! What a glorious morning in America!”

The battles of Lexington and Concord mark the beginning battles of the American Revolution. “Now in ever-widening circles the cry to arms spread over New England. Concord’s bell was heard by Lincoln, Lincoln’s by Carlisle, Carlisle’s by Chelmsford…and so on…Ministers laid down their Bibles to take up their muskets. Schoolmasters dismissed their scholars forever…The fight was to last for six years.”

The next day, Revere was in Cambridge with Dr. Joseph Warren and Dr. Benjamin Church. They had both fought at Lexington. Warren was the president of the Boston Committee of Safety and Revere was hired to be the express rider ready to ride at a moment’s notice.

In Boston General Gage ordered all weapons to be turned in. “It resulted in 1778 firearms, 973 bayonets, 634 pistols, and 38 blunderbusses, which gives an idea of how heavily armed the average citizen was in those days. While Revere was not able to return to Boston his son, Paul, age fifteen was now in charge of the family before they were able to leave.

The Powder-Maker

During the War America was in need of gunpowder. Up until now most of the saltpeter used in Europe for making gunpowder was from Persia or the East Indies. It was important for America to produce her own. The family of Everendon, or Everton, had been making gunpowder from generation to generation. There was only one Everton left who knew how to make it. Joseph Warren received a letter signed ‘True Son of Liberty’ telling of this one. Paul Revere was sent to Philadelphia to gain all the knowledge necessary for making and running a mill for gunpowder. At Philadelphia Revere was put into the hands of Oswell Eve who walked him through the powder mill briefly and showed the mechanics of it. He got a plan of the mill and returned to Canton to build a mill. He is credited “by an almost contemporary source with having overseen the building and the setting up of the simple machinery, but Major Thomas Crane was the man who actually made the powder-…By September (in nine months) he had on hand 37,962 pounds of powder and 34,155 pounds of saltpeter. For the first three years of the war he furnished most of the powder used by the Massachusetts troops.” Revere’s contributions in this field had been more in the mill itself that in the powder, which continued to operate until 1779.

The Soldier and Cannon-maker

In 1776 Revere was now a soldier. He was asked by Washington to go to Castle Island (after the British left Boston) to repair the cannon. Revere “invented a new type of gun-carriage.” Later he was commissioned as a major to help defend Boston. “Revere seems to have had every quality to make an extremely good army officer. He was intelligent, resourceful, tireless. His robustness was both physical and mental and he had plenty of courage…Yet his military record is undistinguished. He certainly had no liking for army life. (If he had, he would have been involved in the battle at Lexington, instead of hauling the trunk, and also, in other regiments.) By fall Revere was a lieutenant colonel and commander at Castle Island…never rising to a higher rank…But if he did not prove a distinguished army officer, there were other things he could do of possibly greater value.

In 1777 with the great need for cannons, Revere was asked to go to “Titicut and make enquiry how they go on in casting Brass and Iron Cannon at the State Furnace under Direction of Mess’re Marguguelle who was Lewis Ansort-the founder of a great modern industry.

“There is reason to believe that even while commander at Castle Island he sneaked back to his own shop now and then to produce a pepper-pot or two and a few small pieces of silver. This was the work he loved…Besides his devotion to his craft and to his family was his equally passionate attachment to the cause of American freedom…His devotion is the more poignant because he had no reward-none of those ‘Victory and Laurels’ we find him generously wishing for others.”

In 1779 there was a campaign which failed at Penobscot. Revere was charged with its failure and charges of disobedience were brought against him. He was relieved of his duty of Castle Island. He was determined to clear his name, for it was not his fault the expedition failed. “His character was more dear to him than life itself…”

In 1781 Cornwallis was bottled up at Yorktown. On October 19 he surrendered and the war of six and a half years was over. (It would be two more years for the peace treaty to be signed.)

With the war over after numerous petitions by Revere for a hearing related to the failed Penobscot campaign Revere was finally given a trial. During the trial he was acquitted. “Revere had persevered and been rewarded with the re-establishment of his character.”

The Supporter of the Constitution

In 1783 around the age of fifty Revere opened a ‘hardware’ shop. He kept in touch with his European connections, cousin, John Revoire, in Guernsey, and a cousin Mathias, near Bordeaux in France. In a letter in 1782 he gave his political views. “If they (parliament) have a right to take one shilling from us without our consent, they have a right to all we possess; for it is the birthright of an Englishman, not to be taxed without consent of himself, or Representatives…(He begs his cousin to come to him in Boston.) That you may enjoy all the liberty here, which the human mind so earnestly craves after…”

“Early in 1788, the Federal Constitution came up for ratification before the Massachusetts Convention. The Boston artisans were strong Federalists (in favor of the Constitution), but they were afraid their leader, Sam Adams would vote against the Constitution. He had not as yet expressed an opinion. A mass meeting of mechanics (artisans) was held at the ‘Green Dragon’. They voted unanimously for adoption and sent an enormous delegation to call on Sam Adams…headed by Paul Revere.” Daniel Webster fifty years later embellished the story a bit but Paul Revere was the leader who presented support of the artisan for the Constitution to Sam Adams. Sam Adams did vote to ratify it.

The Bell-maker

By 1788 Revere decided as a hardware shop keeper to go into the business of producing goods, rather than just retailing them. He built an air furnace and was producing from that along with a silversmith shop on Anne Street. He began a foundry for casting bells. “His first effort was for his own church. (The Old North congregation had joined with the old Cockerel to form the Second Church. Revere offered to cast a bell with no knowledge of how.) He knew that in Abington, shortly before the Rev. Aaron Hobart had set up a bell foundry. Although isolated bells had been cast before in America (especially noted being the Liberty Bell) Hobart is thought to be the first regular bell-caster…When Revere decided to cast bells, he went to Abington…and brought back one of Hobart’s sons and a foundry man…” Much science and art are involved in casting bells. With five hundred pounds of metal from the old bell Paul Revere’s first bell was “panny, harsh, and shrill…But Boston was inordinately proud of this shrieking bell- and so was Paul Revere…He put on his bell, ‘the first bell cast in Boston 1792 P. Revere’ “. In Later years Saint James Church in Cambridge bought it. Paul Revere continued to master the art of bell making. In 1911 Dr. Arthur H. Nichols estimated that the number of bells these two Reveres (son, Joseph Warren Revere) made from 1792 to 1826 could not have been less than three hundred and ninety-eight. Seventy-eight were still in use, forty-seven had cracked. Fire had taken thirty-nine of Paul Revere’s bells, and lightening, two. Five at that time were in museums. The fate of the rest was unknown.” Revere wrote with pride of his bells, “Since 1793 we have cast upwards of one hundred church bells and we have never heard that anyone has been broken or received complaint of the sound…” Some said of his bells, “People venture to prefer it to any imported bell and so did we, but from patriotism.”

“ Revere’s largest and most famous of all his bells still hangs in the stone tower of King’s Chapel…For over a hundred years Bostonians have known and loved this bell…It weighs 2,437 pounds…Boston has not entirely lost its voice.”

The Copper-maker

“Revere’s foundry was surrounded by shipyards. Although he cast so many bells for inland churches, his primary interest was in furnishing the ships. His bells still ring in memory of his skill, but the ‘bolts, spikes, cogs, braces, pintles, sheaves, pumps, etc. he made for the country…Such ship gear had to be made from copper or brass and was largely imported. There were certain secrets about how the amalgam was made up…He went to work to discover how it was done. He was one of very few in New England who knew the secret. He began to make copper for ships, especially war ships.”

There was a great need for an American navy. There was widespread piracy on the high seas in which tribute was being demanded for passage rights. There had been in 1795 a ‘humiliating treaty’ with Algerian pirates to pay them to leave American ships alone. “A popular demand developed for ‘millions for defense, not a penny for tribute!’…The start of the American navy, in 1795, was modest. Three frigates of forty-four guns and three of thirty-six guns were ordered built…The most famous was the Constitution, built at Hartt’s yard close to Revere’s house and shop…Revere was determined to make the copper and brass for these ships…He did furnish the metal for it and the Essex…He made things to last. Some of the large copper blocks were still in use a hundred years later.”

While Revere provided copper bolts he had not provided the rolled sheet copper for sheathing. That was done with British copper. Without copper sheathing bottoms on ships barnacles and sea weed collect and slows down the ship. “Revere saw a chance to make money by being the first man in America to fill this great need of rolling sheet copper. He also saw a patriotic duty and an intense personal satisfaction…This was his most daring venture 9He had had many in his life.), for he put every cent he had into his new works, even borrowed money. He built a mill for making sheet copper using water power…The tide of life runs high. Yet in 1800, he was already sixty-five.”

Paul Revere’s son-in-law, Amos Lincoln was the builder of the new State House, Bulfinch’s State House. It was Paul Revere who provided the sheet copper for its dome. Revere’s only known formal speech was given when the cornerstone was laid on July 4th 1795. He was the president of the new organization later known as the Massachusetts Charitable Mechanic Association. Forty-five different trades were recognized in this organization. Revere’s mills also supplied sheet copper for the roof of the New York City Hall and many other public buildings. (His copper did not include the dome of the nation’s capitol building.)

“In 1803 the war ship, Constitution, (known as Old Ironsides) had been re-coppered by Revere’s copper made in the United States…As she left the shipyard, she was the very symbol of the young republic…her decks of the best Carolina pitch pine, her live oak and red cedar from Savannah and Charleston, her Yankee crew…to her homemade copper bottom…she was typical of the republic,” a true symbol of ‘made in the U.S.A.’.

One other area of Revere’s copper works was the work he did with Robert Fulton. He made the copper for the boilers for Fulton’s steamship. “Much of its success would certainly depend upon its copper boilers.”

The Philanthropist

Of Revere’s generous acts, one to be noted is how he supported an unfortunate son-in-law, Thomas Eayres. He and Revere’s daughter, Fanny, lived in Worcester where Thomas was set up as a Goldsmith. Within two years it became evident that he was a lunatic. Eventually Fanny passed away and Revere took their three children to raise. He tried to get help for Eayres from his own family, but none would help Thomas. Rather than sending him to an almshouse where people were badly mistreated, Revere sought other alternatives and found a new method with Dr. Samuel Willard, a cousin. Willard had done much in humane methods of helping the insane. Revere supported Eayres financially, raised the three children, and took in public outcasts. In 1804 he was influential in getting a pension from Congress for Deborah Gannett. She was the “one woman to fight in the ranks during the American Revolution, a female soldier.” He personally helped her financially in her later life. Revere was involved in many charitable organizations. He was also involved in different offices of public service in the 1790’s. These areas of contributions left their mark on society along with his great work as a Patriot during the dawning of the new nation.

Conclusion

It is difficult to summarize the life of such an active, productive patriotic individual who contributed so much to our nation. He was more than just the rider of a poem, which made him immortal in our memory. Yet, without the poem, for which we are grateful to Longfellow, the details of his work may have gone unnoticed. His life was woven into the very fibers of the cloth from which our nation was cut, through his leadership, involvement, and his love of liberty. His multi-faceted abilities and energy are a great example of industry and work ethic much needed today.

Forbes wrote, “A man might make a spurt now and then (like that ride to Lexington), and that would be remembered but most of life (and he knew it) is the unromantic courage and quiet heart that can still ‘trudge’ on’, (a phrase taken from a poem written by Revere describing his day to day calmer simpler things)… At the time of his death he was not yet a legend- that would not happen until Longfellow’s poem. He had lived an honorable life of usefulness.”

I trust as we reflect upon this one individual we will take courage to labor in our own spheres of influence and abilities for the cause of liberty in America and the world. As Paul Revere was a messenger who carried principles of free government "in his saddlebags" we too can communicate these principles in our nation today. I hope you will find a bit of hope for your heart as you read of Paul Revere. “…Proclaim liberty throughout all the land unto all the inhabitants thereof…” Leviticus 25:10

Happy Listening,

Peggy White (Editorial Staff, Liberty Lantern)

Portrait of Paul Revere painted in 1768, age 33, by John Singleton Copley |

|

Statue of Paul Revere on a horse in a small park in front of the Old North Church, Statue was made by Cyrus Dallin, unveiled in 1940 (Dallin- an American sculptor and Olympic archer-received bronze medal in St. Louis, 1904) |

|

The Third Lantern, a replica of the two displayed in the steeple April 18, 1775, was dedicated by Pres. Ford in 1975 as a symbol of hope for freedom. |

Old North Church, 193 Salem Street Boston, Mass. The historic church, in whose steeple was hung the signal lights for Paul Revere’s famous midnight ride. |

Questions for reasoning:

1. What are three key character qualities seen in the life of Paul Revere? Give evidence of these qualities through examples in his life.

2. What was one influence upon Revere’s ideas of civil liberty?

3. How did Revere demonstrate as a young boy his understanding of self-government? (Identify the principles of government.)

4. Give examples of how God providentially protected Paul Revere.

5. What event caused King George III to order the capture of the American leaders at Lexington and the seizure of munitions at Concord?

6. Identify Paul Revere’s contributions to America.

Resources and works cited:

1. Paul Revere and the World He Lived In by Esther Forbes

2. Paul Revere’s Ride by David Hackett Fischer

3. Paul Revere, Son of Liberty by Keith Brandt, illustrated by Francis Livingston (children’s book)

4. And Then What Happened, Paul Revere? By Jean Fritz, illustrated by Margot Tomes (children’s book)

5. Christian History of the Constitution, Christian Self-Government by Verna Hall

6. Paul Revere’s accounts of the Ride

7. www.paulrevereheritage.com